Breaking Through

Chris Patterson wasn’t supposed to survive the streets of Spokane. Now he’s helping others stay off them.

By Dave Meany

The words left quite an impression on the young Chris Patterson. They stand out as one of those pivotal life moments many of us look back on as a possible turning point. Only this wasn’t a motivational speech. Things hadn’t really turned. Yet. But the words have stuck with him all these years: “I wouldn’t be too concerned, because Chris isn’t going to live to see 18.”

The year was 1984. The words came from a state social worker tasked with delivering a 13-year-old Patterson to a new foster home in Spokane.

“I think the lowest point is when you start to realize, it’s just you… and you’ve got to figure it out,” Patterson says quietly. “And there is really nobody else there to do the work, and so you’ve really got to get up off your backside and do what you’re supposed to do. Or you’re going to sink.”

On that day Patterson, a self-described “runner,” a street-wise kid who was proud that he never stayed put in a foster home, was doing nothing but sinking: “I wouldn’t be too concerned, Chris isn’t going to live to see 18.”

“It sort of hits you,” he recalls. “I knew that I was hanging around with a lot of the tougher crowd, getting in fights almost every day.” He knew, in short, that the social worker had it right.

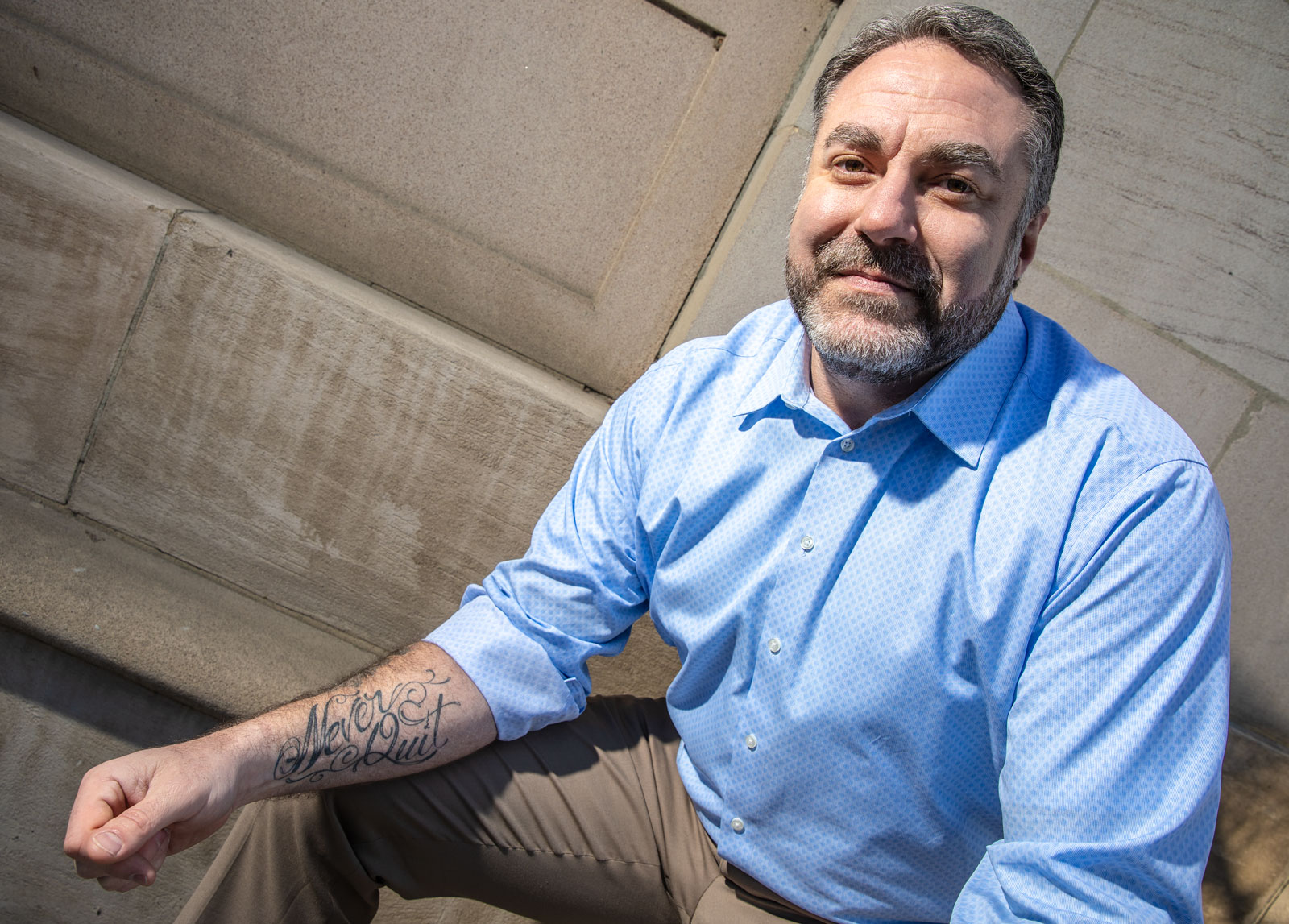

Patterson still doesn’t look like the type of guy you’d want to pick a fight with. A full framed, 6-feet, 5-inches tall, he cuts an imposing figure. His office wall is adorned with the mounted head of a wild boar that he shot in California. Dozens of hunting photos and souvenirs add to the tough-guy aura.

But it’s not the whole picture. His workspace also includes a framed drawing from his young daughter, along with a set of her sweetly smiling class photos. There are awards from Leadership Spokane and Rotary International, both signifying Patterson’s deep involvement in the community. There is an image of Patterson standing alongside U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a testament to the broad reach and wide recognition his work has gained. And there is a bright red banner from EWU, a prominent reminder of the place that helped him to become the man he is today; a person who is, in fact, deeply concerned about each and every youth who may not live to see 18.

Patterson, who recently turned 50, owns BreakThrough, Inc., a state-supported agency that operates 10 residential service homes for children who resemble his former self, at-risk youth from here in the state of Washington, most of them living in the Spokane and Tri-Cities areas.

“We deal with the most intense population that there is in the state,” he says. “A lot of those kids that come to us can’t be returned to a foster home at the time, they have to actually work with their behavior management. Some of these kids can be pretty destructive to their own path, their own future and to themselves as well as maybe other people. They are really, really challenging to work with until you can figure them out, get them stable.”

“I think his past experiences definitely have a huge factor in how he operates the business,” says Marcus Kelsey, BreakThrough’s quality-assurance manager who oversees the Spokane-area programs. “That’s the reason I came to this company. I was drawn.”

Kelsey’s own life experiences are another reason he was likely drawn to BreakThrough. He also grew up in foster care, living in California and Montana before coming to Spokane. And, like Patterson, he also earned a degree from Eastern, studying visual arts. Kelsey’s path took a turn after he befriended a classmate with multiple sclerosis during his freshman year, helping to care for him during their time on campus. This eventually led Kelsey toward helping at-risk populations. “This is kind of natural to me,” he says.

It’s a natural fit for Patterson as well, who says he loves every minute of his challenging vocation. He knows the road these children have traveled. And he believes he knows how to get them on the right path, even if it means working on seemingly small things like table manners and proper hygiene.

“It’s not a one size fits all,” Patterson says. “Every client has his or her own unique way or specific needs, so we develop a plan for each one.”

After Patterson had his revelatory moment at age 13, he gradually began to develop a plan for his own success. College was a big part of that plan. After graduating from Riverside High School north of Spokane, he entered the Job Corps’ forestry program outside Curlew, Washington — a gig that helped him save tuition money by spending long hours working the fire lines at places like Yellowstone National Park.

His first stop after returning home was Spokane Community College, where he earned multiple associate’s degrees while studying fire science, administration of justice and liberal arts. At the urging of a friend, Patterson decided to try a four-year institution. Being from Spokane, he says Eastern was an obvious, and fortuitous, choice. “It definitely opened up other doors that I didn’t have before.”

Although at one time he thought he might try law enforcement, by the time he enrolled at EWU Patterson knew he wanted to pursue a career that was closer to his heart — social services. He quickly immersed himself in special education classes and still remembers some of the EWU instructors who pushed him to succeed, especially Ron Martella, then a professor of education, and Martella’s wife, Nancy Marchand-Martella, a professor in the departments of applied psychology and counseling, educational, and developmental psychology.

“I remember him because of his motivation,” says Martella, now a faculty member at Purdue University, where his wife is the Suzi and Dale Gallagher Dean of Education and a professor of special education. During a recent phone conversation, Martella instantly recalled Patterson’s enthusiasm and commitment to learning.

“He was incredibly inquisitive,” Martella says. “He would be one that would come into the office quite a bit to talk about the material and how you apply it. And so he was always wanting to know more than what was going on in the class.”

Martella spent more than 20 years at Eastern teaching special education and behavior management classes, and still takes pride in the program he left behind. He believes proper training is the key to running successful behavior programs like BreakThrough. Martella thinks Patterson learned critical behavior analysis methods at EWU that are even more relevant to the occupation today.

“You have to have those skills in order to deal with those issues, and he gained those skills in the program,” says Martella.

During the course of the conversation, Martella spoke glowingly of the many former EWU students, like Patterson, who are making differences in their communities. He says he has kept in touch with Patterson over the years, even doing consulting work for him on a few cases when he first started his work.

Patterson is thankful for what Martella and his wife did for him at Eastern. “I always respected them,” he says. “They were straightforward, to the point. They taught you, they wanted you to learn, and they wanted you to be successful. And it wasn’t just ‘here read the book and have a test.’ We went over laws, we went over WAC’s, we went over RCW’s, we went over everything there was to know about special education law.”

Patterson graduated from EWU in 2011 with a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary studies and a minor in childhood educational psychology. The expertise he acquired led to jobs in private group homes for children, as well as work involving special programs for developmentally disabled adults.

“The more severe the client was, the more I enjoyed the job.”

With his EWU degree in hand, Patterson worked in the industry until he was ready to start his own business helping troubled kids and their families. “I love it,” he says. “I think the biggest challenge, it’s not the kids. We know why the kids are here and we know why we’re supposed to be working with them. It’s just getting the rest of the adults in the room and the professionals and legislators and everyone else to figure it out.”

Martella seems certain Patterson had things sort of figured out during his Eastern days when he talked about running his own program. “This goes back to when he was a student and that’s one of the reasons why he was driven to learn the material so well because he already had a goal, I believe, of doing something like this when he was a student,” Martella says. “So it doesn’t surprise me at all.”

“He always showed a lot of tenacity in classes and when he started his business.”

BreakThrough now holds two contracts with the state. One, for the residential homes, was developed with the Division of Developmental Administration. The other involves work with the Department of Children, Youth and Families. The business employs more than 100 people, including Kelsey, the quality assurance manager.

“He (Chris) has an unorthodox approach, but I think it’s very fitting. He cares about the kids,” Kelsey says. “I’ve worked with other companies, and I think with him there is a little more empathy, compassion, just because he can relate. He’s been on both sides of the fence, if you will.”

With its low youth-to-staff ratio, BreakThrough aims to help their young clients develop critical social skills such as personal accountability, workplace responsibility and appropriate family communications. Many of the children have learning disabilities or serious behavioral issues, so individualized treatment is supplemented with special programs at school and at home. Patterson must also navigate complicated state regulations and codes to ensure it all runs smoothly.

The name BreakThrough came from Patterson’s wife, Dalene, who noticed her husband would come home and talk about how much of his work involved developing the right program to help troubled youth break through barriers.

There are a lot of barriers to break. According to the policy and advocacy group Partners for Our Children, more than 9,200 children in the state of Washington need some type of care —from foster care to group care. In Spokane County, 9.1 children per thousand are in need of care, the highest rate in the state.

These daunting numbers are no deterrent to Patterson, who nevertheless acknowledges his efforts are typically just a first step in a process where success is hard to measure.

“Success is measured for each kid. And it could be an hour at a time, a day at a time or a month at a time,” he says. On a personal level, success can also come from a simple phone call that reminds Patterson he’s giving back to a system he himself was able to navigate and survive.

“I’ve got kids that I worked with 20 years ago that will find a way and they will call me. They call to say ‘hello,’ to see how things are going. And then they say, ‘I’m sorry.’ Their consistent answer is that they’re sorry they didn’t listen. And they appreciate the fact that someone was there to go toe to toe with them at that worst moment — that moment when they were being the worst possible kid — and I didn’t back down and give up on them.”

Maybe that’s why the tattoo on Patterson’s right forearm is so meaningful. It reads “never quit.” It’s one of his favorite sayings, a “life rule” for both for him and the youth he serves. It’s also a reminder that he didn’t quit on himself after hearing those words so many years ago: “I wouldn’t be too concerned, because Chris isn’t going to live to see 18.”

Filed Under: Alumni Profiles Featured

Tagged With: Spring/Summer 2019