A Half-Century of Smiles

Over its 50 years of service, Eastern’s dental hygiene program has helped students pursue a passion for dental health.

By Melodie Little

Eleven years after fleeing cartel violence in his Mexican hometown, 22-year-old Carlos Valdovinos, a newly minted graduate of EWU’s dental hygiene program, is ready to start making a difference.

Valdovinos is the first among his 10 siblings to earn a university degree. As he walked across the stage at Eastern’s semester commencement ceremony in May — his proud mom in the audience after making the trip from central Mexico — he reflected on how it all began.

“As soon as I saw what a dental hygienist does, of how big of an impact I could bring to a diverse patient population, I just fell in love with hygiene,” he says.

For 50 years, EWU’s Department of Dental Hygiene has helped more than 1,600 graduates like Valdovinos pursue their passion for improving the oral health of thousands of patients.

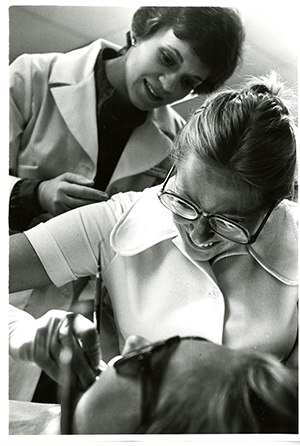

The work starts while they are still in school, as advanced students hone their patient-care skills by providing free and reduced-price dental services at the EWU Dental Hygiene Clinic.

The 46-chair clinic is located in the Health Sciences Building on the University District campus. Most of its patients have either state-subsidized health plans or lack dental insurance. Through the years the clinic has developed expertise in serving high-risk groups, including those with diabetes and pregnant women. In addition, the clinic treats children and adults who are medically fragile and need accommodation, such as those with autism.

“We are a safety net for low-income and aging populations,” says Lisa Bilich ’89, professor of dental hygiene and department chair, who joined EWU’s faculty in 2002. “I know Eastern is making a positive impact.”

“We are a safety net for low-income and aging populations,” says Lisa Bilich ’89, professor of dental hygiene and department chair, who joined EWU’s faculty in 2002. “I know Eastern is making a positive impact.”

It’s a role that shouldn’t be underestimated, says Francisco R. Velázquez, health officer for the Spokane Regional Health District. By providing access to oral care for disadvantaged members of the community, he says, the dental clinic significantly impacts the health of the people it serves.

“The importance of good oral health is often overlooked; the health of your teeth and gums has a major impact on your overall health and quality of life. Poor oral health can impact how we see ourselves, and how we are seen by others,” Velázquez says.

Understanding the role of dentistry in human wellbeing has long been a central tenet of Eastern’s dental hygiene program, though much has changed since the program was first accredited in 1972.

At the time, EWU’s tuition was $360 per quarter, streakers sprinted through campus and dental hygienists mainly took X-rays, filled cavities and polished teeth. Notably absent was an established link between dental decay and illness, such as endocarditis, cardiovascular disease and pregnancy complications.

The cause-and-effect, once discovered, would dramatically change the role of dental hygienists, Bilich says, opening the door for program graduates to become respected members of health-care teams inside hospitals, medical clinics, therapy centers and in the field of public health.

Take the link between diabetes and periodontitis, Bilich says. Not only is diabetes a risk factor for periodontitis, if oral health disease is left untreated it can have a negative effect on glycemic control. So, she says, treating periodontitis boosts patients’ ability to manage diabetes.

EWU’s dental hygiene program’s job-placement rate is well over 90 percent, program statistics show. Typically, only those students who take time “to explore their options” are not hired right after graduation. Notable EWU alumni include Jessica Scruggs ’13, who earned a master’s degree at EWU and served on its faculty before working as special assistant to former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy; Katie Glueckert ’17, who serves with the Montana Hospital Association as its South Central Montana Area Health Education Center director; and Camille Luke ’07, ’10, the current president of the Washington Dental Health Association.

“The downtown clinic was great because we could offer services to different kinds of organizations where the need was great for underserved people who had dental problems,” McHenry says.

Diane McHenry, who helped to establish the dental hygiene program and taught students for 28 years before retiring in 1999, says she is amazed by the advances in technology, techniques and dental materials, as well as the expanded capabilities of the university-operated clinic.

McHenry fondly recalls the program’s humble origins, when administrators at what was then Eastern Washington State College sought to address a severe shortage of hygienists in Eastern Washington. At the time, McHenry was working in a Cheney dental practice. She was tapped to serve on an advisory board, then asked to join Eastern’s faculty and help launch the degree program.

Things didn’t go smoothly. In order to admit its first students, the program needed to transform the band room in the (now-demolished) Rowles Hall into a teaching clinic with offices. A construction delay created a scramble for temporary space.

The local dental society was nudging the university to start classes right away, and the faculty was scrambling to find the space: “We had seven students but we didn’t have any facility,” McHenry says. “So, we were able to find a room in the Science Building that was an old lab. It was dingy and dark, and there was an aquarium in there with some kind of a big fish in it that we fed once a week.”

Two quarters later, the renovation was finally completed and a 17-chair clinic opened at Rowles Hall. Although everyone was “very happy to move in,” McHenry says, program faculty members began to realize that, because the clinic served mostly healthy young students, their hygienists in training were missing out on key learning opportunities.

Thus began the program’s push to provide its students with a more comprehensive patient-care experience while serving the greater community — an effort that culminated in EWU opening a 15-chair clinic on the second floor of the Paulsen Medical and Dental Building in Spokane in 1977.

“The downtown clinic was great because we could offer services to different kinds of organizations where the need was great for underserved people who had dental problems,” McHenry says.

In 2002, the program moved from the Paulsen Building into a state-of-the-art clinic in the Health Sciences Building, a half-mile away. Today, that clinic is staffed by nearly 80 juniors and seniors who work with supervising faculty members and two local dentists, Rachel Deininger and Amy Clement. Of the nearly 8,400 patients served through the clinic, some 6 percent are children and 24 percent are over age 60.

Anna Warrington is among the seniors receiving care through the EWU Dental Hygiene Clinic. The 84-year-old Spokane resident has been coming to the clinic for three decades now: “When I first started coming, it was in the Paulsen Building,” Warrington says, “I met my very first dentist in Spokane through the clinic: Robert Parker.”

Warrington says she comes twice a year for checkups, and receives three to four cleanings annually. She credits the clinic, which has provided her with periodontal treatment, fillings and other restoration work, with helping her keep her original teeth in good shape.

“I just love this clinic. I love all of the people who work here, and the students, too. I would recommend them to everyone,” Warrington says.

EWU’s budding hygienists increasingly represent the diversity of the community they serve. Dental hygiene was among the first departments at EWU to move to “holistic admissions.” The holistic process involves looking beyond traditional markers for acceptance — such as grade point average and standardized testing — to also consider harder-to-measure factors that point to success in the classroom and clinic.

“That means our students are more than a grade,” Bilich explains. “They bring their backgrounds and that helps them interact with our patients, and that really is very important to the community and to our low-income and ESL students. It’s just a win-win situation for everyone.”

For Valdovinos, holistic admissions recognized his fluency in English and Spanish, as well as his outstanding work ethic. “He works probably twice as hard as other students because English is his second language,” says Bilich.

Valdovinos brings other qualities to the table as well. He is both humble and overwhelmingly supportive of his peers. Perhaps most important, his work with patients of all backgrounds is exemplary.

“He understands they are not just a grade, and they are not just a number. He treats them with kindness and respect — every patient he has,” Bilich says. “He just exemplifies why we want to continue with holistic admissions.”

Valdovinos brings other qualities to the table as well. He is both humble and overwhelmingly supportive of his peers. Perhaps most important, his work with patients of all backgrounds is exemplary.

Valdovinos has overcome tremendous obstacles. He was just 11 years old when his parents sent him to live with an older sister, Jovita, in Yakima, Washington. It was a tough decision, but one made necessary given the risk of staying put. Coalcomán de Vázquez Pallares, the Valdovinos’ picturesque hometown in Mexico’s Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range, was increasingly under threat from cartel violence. Shakedowns, kidnappings and murders were routine.

“It was pretty common for us as kids to see big trucks coming down the road loaded with guns and men, or multiple funerals all over for unknown reasons,” he says, adding, “there was just violence all around us.”

Throughout his four years at Eastern, news from home was filled with accounts of disappearances and deaths. At times, the sadness was so overwhelming that he felt like giving up.

“The faculty here have helped me calm myself. [They] reminded me why I am here, of the friendships I’ve made and all the important things that have happened along my journey which led me here,” Valdovinos says.

The dental hygiene team also helped Valdovinos find his way academically. Though a gifted student who had excelled back home in Mexico, and in math classes taken throughout his schooling in Yakima, reading and test taking in English sometimes posed challenges. Bilich and her team connected him with a mentor and a study group. Valdovinos embraced the intervention, working hard alongside classmates. Along the way his leadership skills emerged, and he became president of EWU’s Student American Dental Hygiene Association.

In addition to academic challenges, Valdovinos and his classmates also faced pandemic-related obstacles. In the spring of 2020, for example, as the pandemic maxed out hospital beds and forced the temporary closure of dental practices and clinics, graduation for that year’s seniors was threatened.

Eastern’s dental hygiene team stepped up to help, working with their accrediting agency to find a solution. “I’m so proud of our faculty for pulling together and writing an accreditation report. And, we graduated the class of 2020 on time,” says Bilich with a smile. “That was the biggest accomplishment we had during the pandemic.”

For his part, Valdovinos makes a point of crediting the generosity of scholarship donors who, from his start at Eastern, helped him to connect with his passion and ultimately earn a degree: “I would have never been able to get my education if it had not been for the donors who helped me financially.”

“I decided to pursue an education to hopefully change the future for other generations,” he says. “I feel like I am a positive role model for my family and friends. My biggest hope is that more will decide to find their true passion and change the course of their lives for the better.”

Tagged With: Spring/Summer 2022