A New Era of Discovery

With its Science Building renovation nearing completion, Eastern’s polytechnic future comes into focus.

By Charles E. Reineke

Back in 2022, just three weeks after the inauguration of EWU’s gleaming new Interdisciplinary Science Center, construction began on the renovation of the 148,000-square-foot Science Building next door.

The second and final phase of that $110 million project is now nearing completion, its new laboratories, faculty work spaces and areas for student engagement just months away from full occupancy. When the final ribbon is cut and all the doors opened, the conjoined Science Building and Interdisciplinary Science Center will represent the culmination of perhaps the most significant research and development investment in Eastern’s history, one that promises to usher in a new era of faculty discovery and student learning.

For an institution now proudly known as the region’s polytechnic, the moment represents a watershed, albeit one occurring during a period of significant political headwinds for higher education and scientific research.

Eastern’s new chief academic officer, Provost Lorenzo Smith, joined EWU earlier this year after serving in a similar position at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas. Smith holds a PhD in engineering, and arrives at Eastern with a distinguished background as an educator, entrepreneur and researcher.

“I really have a passion for teaching,” Smith says. “But when I learned about the polytechnic designation, it got me very excited because it showed that EWU is a hands-on type of institution. Very applied. And to me, that’s where the rubber meets the road.”

While the term “polytechnic” typically conjures up images of engineering labs and computer-science classrooms, Smith emphasizes that applied learning has a place in every field — from English majors working with nonprofits, to history students identifying racially restricted property deeds. It’s all about applied learning, he says, taking classroom knowledge and putting it to work in internships, capstone projects and community partnerships.

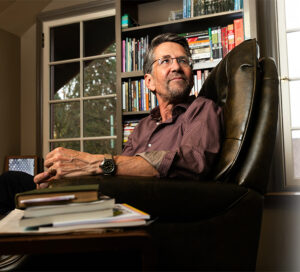

Research faculty members such as Jason Ashley, an associate professor of biology who specializes in the cellular and molecular processes involved in bone generation, is fully on board with the polytechnic transformation. But for now, he’s focused on facilities.

“We’ve been able to make good progress on our research projects in our temporary spaces that are spread across the Interdisciplinary Science Center, but I’m excited to have everything centralized.”

Resource upgrades, he says, are only the beginning. “Another benefit of the renovation will be to bring all biology faculty back into a single building. I’ve found that some of my most exciting ideas came from spontaneous discussions with my colleagues from biological disciplines that are quite different from mine.”

For Ashley, the state’s investment signals something important about EWU’s trajectory. “I think that the investment in our research infrastructure is a sign that we’ve gotten better at showcasing what we accomplish and what more we can achieve with the right resources,” he says. Like Smith, he doesn’t see this as a departure from Eastern’s teaching mission. “As a scientist, I welcome a greater institutional interest in research and development. Our students’ learning isn’t limited to classrooms, and an increased research capacity will create more educational opportunities for them to develop critical skills.”

Yet even as EWU invests in its research future, headwinds have been gathering at the federal level. The current administration has taken a markedly different approach to federal research funding than previous administrations of both parties, calling into question decades of bipartisan consensus that university-based research is crucial to American innovation, economic strength and national security.

According to the American Association of Universities, federal science budgets for three major research funders, the National Science Foundation (NSF), Department of Energy, and the National Institute for Standards and Technology are at a 25-year low, while additional grant-making agencies across the government have also found themselves under fiscal pressure.

Other nations, meanwhile, are ramping up their spending. According to recent data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, China, for example, is rapidly closing their deficit with the U.S. in research and development spending, potentially reshaping the balance of scientific power.

Cuts and priority changes at NSF are particularly concerning to EWU faculty members such as Charlotte Milling, an assistant professor of biology at EWU. Milling and her students are part of a multistate effort to preserve the critically endangered pygmy rabbit, along with the sagebrush ecosystem that it depends upon for survival.

Earlier this winter, Milling and her project collaborators at the University of Idaho submitted a $500,000 grant proposal to NSF. Their aim is to use the funding to better understand how sagebrush-dependent animals and plants are responding to climate change. The timing was fraught: The application was due just days after the presidential inauguration, and Milling knew that during the incoming president’s previous term, language related to climate change had been scrubbed from NSF funding lines.

“We had a list of words that were flagged, basically saying: ‘you can’t be using these in any of your applications,’” Milling recalls, adding that this left researchers in the dark on key questions. “How fluid is this list? Is ‘climate change’ going to hit it? I mean, we were applying for a climate-change-specific grant.” Despite the uncertainty, she and her colleagues carried on. “Both my collaborators and some of my colleagues here at Eastern just emphasized: Until you hear otherwise, pretend like it’ll go through,” Milling says. “Invest in putting it together.”

The application did, in fact, go to reviewers at NSF, where it received positive feedback. Milling remains hopeful that the proposal, if not now then at some point, will be approved. “No work that we do is ever wasted. It’s always an investment in the future,” she says.

Still, concern for that future is a common theme among university-based scholars and scientists, especially those early-career faculty researchers who feel they’ve been left, as Milling puts it, “without a road map.”

There are also questions around the training of those who have yet to begin their careers — federal grant support is typically the driver for funding graduate and undergraduate research assistants. Without that support, investigators like Milling fear we may find ourselves struggling to fill the ranks of next-generation scientists and scholars.

For Ashley, too, the sense of uncertainty is palpable. He currently receives funding from a National Institutes of Health grant that’s designed to support research at primarily undergraduate institutions. It funds his investigations while also providing tuition waivers for graduate students.

“I’ve got a little over two years left on this grant, which means it’s time to start writing a renewal to avoid a lapse in funding,” he says. “I hope that the R16 mechanism that I’m currently funded under continues. Otherwise, it will mean fewer graduate and directed-study students.”

Nicholas Burgis, professor and chair of chemistry, biochemistry and physics, finds himself in a similar situation. The current three-year extension of his NIH grant, which funds the molecular-level investigation he and EWU Professor Yao Houndonougbo are pursing into a rare but lethal genetic disorder affecting infants, is moving forward. But worries remain. “Research is a very challenging and time-consuming endeavor,” Burgis says. “Additional barriers to participating in that endeavor will only leave the USA behind the competition. I have serious concerns about future funding and my ability to take the next steps necessary to advance my research.”

Students these days are wise to the challenges. Ashley says he used to assume they didn’t pay much attention to the intricacies of research funding. “But our students are now acutely aware of how science and education policies can directly impact their experiences as students and their future careers,” he says.

Burgis echoes this sentiment, particularly when it comes to STEM workforce needs. “We have to pass the torch. The Boomers are retiring and Gen X is a smaller generation. There will be lots of vacant jobs, especially considering our leaky pipeline from high school to professional positions.”

“The open nature of academia encourages collaboration and sharing,” he continues, “unlike the environment of corporate America. We can’t simply shift innovation to businesses. They don’t have the capacity to do it at scale, and they carefully guard their intellectual property.”

For his part, Provost Smith recognizes funding uncertainty requires universities to be more strategic and diversified in their approach. By focusing on teaching and learning — along with applied research with community partners and undergraduate research experiences — Smith says EWU can play to its strengths while reducing dependence on federal grants and contracts. Smith also makes a point of emphasizing the value of research to the public. “We have to show that higher education is worth it,” he says. “And I think the polytechnic model helps us do that because we’re very focused on applied learning, on career outcomes, and on partnerships with industry.”

“In strictly economic terms, every dollar the NIH spends generates more than two dollars of economic activity; the only federal spending that beats that return is education. Support of university research accomplishes both,” Ashley says.

This line of reasoning is not new. In the months just before the end of WWII, Vannevar Bush, a leading intellectual who served as president of Carnegie Science, submitted a landmark assessment of how the United States might best position itself to thrive in the post-war world. His report, Science: The Endless Frontier, made two key points: that scientific research was vital for the country’s continued security and economic well-being, and that governmental, industrial and academic research could create far more value in partnership than in isolation.

Think of today’s research as a great return on the investment envisioned by Vannevar Bush, both Burgis and Ashley say. “In strictly economic terms, every dollar the NIH spends generates more than two dollars of economic activity; the only federal spending that beats that return is education. Support of university research accomplishes both,” Ashley says.

Recent studies back them up. According to a new report from the nonprofit United for Medical Research (as cited by the Harvard Gazette), every research dollar funded by the National Institutes of Health delivered just over $2.50 in economic activity. In the previous fiscal year, the report found, NIH awarded more than $36.9 billion to researchers whose work supported more than 408,000 jobs and generated over $94.5 billion in new economic activity nationwide. Closer to home, the report found that NIH expenditures in the state of Washington totaled some $1.2 billion and supported 12,250 jobs.

Ultimately, however, the case for university research needs to rest on more than economics. “Our students are doing fantastic work and, if we showcase that, people will notice,” Ashley says. “If we continue to make necessary investments in faculty and infrastructure, I’m confident we can both grow our research corpus and continue to produce graduates that thrive.”

Seven months into his tenure, Smith also remains upbeat. “Yes, we have a long way to go. Not because we haven’t done a lot, but because we have very high aspirations. We just have to continue to reinforce how seriously we take applied learning here at EWU, and how we want to grow it. I’m feeling good about the future.”

Filed Under: Featured

Tagged With: Fall/Winter 2025-26