Where the Story Started

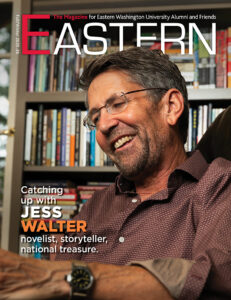

Jess Walter reflects on how class, ambition, and a fifteen-dollar decision shaped his path to literary stardom.

By Charles E. Reineke

The backyard of Jess Walter’s house on Summit Boulevard isn’t huge, but there’s plenty of room to spread out. To the left is a patch of close-cropped lawn; on the right a concrete patio next to a tarp-covered swimming pool.

Back near the alley sits a carriage house, constructed circa 1910. It’s been beautifully restored, with double-wide doors and sturdy, river-rock walls. This is where Walter ’87, arguably Eastern’s most famous alumnus, creates the work that has made him a beloved, best-selling author. The “office,” he likes to call it.

The writing happens in the loft above the place where the carriages used to go. It’s a comfortable space, nothing fancy. There’s a plain wooden desk and a black office chair. A computer and a monitor. A saggy cinnamon-colored couch for napping; an upholstered leather armchair for reading.

There’s also, lined up under a sloping part of the ceiling, an untidy stack of cardboard boxes. Most are of the bankers’ box variety. Others are shoeboxes left over from the kicks that Walter, a basketball fanatic and keen student of the game, wears when shooting hoops. He’s got on a pair of low tops now.

It’s an unseasonably warm day in November. Looking fit and relaxed, Walter chats with a reporter and photographer as he approaches the line of boxes, a three-inch-thick sheaf of unbound paper in hand.

Turns out the boxes are filled with notes and ideas for new projects, along with manuscripts for most of the many books he’s published. The papers are the typescript for So Far Gone, his latest novel, a work published to universal acclaim just a few months ago. “Like closing a door,” he says as pages drop down and the box-top goes on.

“A lot of these are full of notes for projects I want to work on,” he says, surveying the pile. “They all get thrown in there, and they eventually become drafts.” It’s not the sort of filing system one would expect of a writer who has published short stories, essays, criticism and eleven books. One who has been a finalist for the National Book Award and a Pulitzer, won an Edgar Award, and has written four bestsellers, including Beautiful Ruins, which reached No. 1 on The New York Times list. But, clearly, whatever Jess Walter is doing, it’s working for him.

It’s been just under a decade since Eastern magazine last visited with Walter. He’s still in Spokane, the place where he was born, grew up and, against what might have seemed like long odds, traveled down the road to EWU. “I’ve just turned 60, and it’s my 30th year of publishing,” he says. “You start to look back, to think about which things are important.”

Eastern, Walter says, is very much one of those things. The working-class son of a pipefitter, Walter was the first of his family to go to college. A smart kid who loved to read, both his mom and dad encouraged him to get a degree. It was his dad, however, that made him an Eagle. Walter likes to tell the story when he gives public lectures and readings. Never fails to get a laugh.

It goes like this. After being advised by a counselor at East Valley High School that his exceptional SAT scores made him a can’t miss college prospect, Walter came home from school one day with applications from the University of Washington, Washington State and Eastern.

“I said to my dad, who was going to help pay for school, ‘alright, these are the places I want to apply.’” His dad pointed out that each of the applications cost $15. “So pick one!” his dad said. “Well, I guess the University of Washington,” Walter said. “That one’s too expensive,” replied his dad.

“Washington State?”

“Nope.”

“How about Eastern?”

“Good choice!”

The decision made, Walter was admitted to EWU and its Honors College. There he thrived while studying under academic luminaries such as the late English professor Don Wall, while at the same time reporting for The Easterner student newspaper. It was at EWU that he also began the single-minded pursuit of what Walter describes as his “improbable dream,” that of becoming a professional writer of fiction.

It was never easy.

At age 19, Walter and his girlfriend, Danette Driscoll, also an Eastern undergraduate, discovered they had conceived a child. They’d only been dating for five months. Walter proposed, they got married and Danette ’87, ’03 gave birth to a daughter, Brooklyn (today age 40, an educator with a PhD in English). Both parents, now amicably divorced, stayed in school and graduated in four years. “I was so proud of us,” Walter says of his parenting experience. “I came back from class one day with a sweatshirt that said, ‘Eastern Dad.’ I said to my wife, ‘Look! They make sweatshirts for guys like me!’”

She was only mildly amused. “I’m not sure you are the type of dad they had in mind,” she said.

Even at the time, Walter knew having a daughter was going to change things. He made the most of it. “Suddenly, when you’re 19, just turning 20, you’ve got another human being relying on you. Your ambitions move to another level,” Walter says. “I had always been ambitious as a writer, but now I had to get serious about paying the bills.”

He worked at Gatto’s Pizza. He wrote tickets for EWU parking and transportation services. He even had a security gig on campus. “It was a job I could do from midnight to 2 a.m.,” he says.

All the while, Walter moved forward with his studies and his work at The Easterner. Success at both led to an internship at The Spokesman-Review, a prized gig in those days. After graduation, Walter parlayed this foot-in-the-door start, followed by a long string of unpaid positions, into a staff job.

“Even getting in at The Spokesman was a leap,” he recalls, adding that The Spokesman in those days almost exclusively hired young writers from the nation’s top journalism programs. Walter never doubted, at least not outwardly, that he was as good as any of them.

“You first want to prove yourself as a reporter,” Walter recalls, pausing for a moment before continuing. “And I was also reading all the time, thinking about that other, secret desire to be a novelist. This all sounds now like it came from a place of confidence. It probably came from the opposite place; a place of deep insecurity, a desire to prove yourself.”

Walter admits he began his career with a chip on his shoulder, a need to show that an EWU grad could play with the big boys. He knew there was a class system out there; that meritocratic principles were often little more than window dressing. It kind of pissed him off. “You want to show up everyone who went to a ‘better’ college, you want to show everyone who’s on the list of best novels of the year that you belong. At some point that insecurity shifts to something a little healthier. I don’t know that it ever lands totally in the land of confidence, but it’s just offshore.”

At The Spokesman, it took a while before his newsroom colleagues caught on that the kid from Eastern had staying power. But after grinding through the internships and unpaid gigs, he finally merited a graveyard shift on the cops-and-courts beat. Walter loved it, filed good stories, and soon moved up to daytime work. A couple of years later, his big break came.

In the summer of 1992, word reached Spokane of an armed standoff across the state line in rural Boundary County, Idaho. Soon the entire nation was transfixed by what became a deadly siege at Ruby Ridge, as federal agents sought to enforce a firearms warrant against a resistant Randy Weaver and his well-armed family.

Through the type of dogged reporting that would be at home in one of his novels, Walter — even though he wasn’t initially assigned to the team working the story — managed to track down a relative of the Weavers that the FBI was about to bring to Ruby Ridge to speak with the family, mid-siege. That point of contact, which led other family sources to open up to him, turned out to be a major reporting breakthrough, one that helped bring to light facts that complicated — to put it mildly — the narrative offered by federal officials.

Walter’s reporting on the siege and its aftermath eventually became the basis for his first book, Every Knee Shall Bow (reissued as Ruby Ridge). That non-fiction title, both a critical and commercial success, remains the definitive account of what many now recognize as a watershed moment in contemporary American history. It also showed, with its expertly drawn character sketches, perfect pacing and keen eye for detail, that Walter was a born storyteller. No accident that several critics pointed out that the book “reads like a novel.”

Ralph Walter ’91, Jess’ younger brother, is today the sports editor for The Spokesman-Review. He says no one in the family was particularly surprised by Jess’ successes. Even as a little kid, it was obvious there was something special about him.

One early anecdote stands out, Ralph says. They were at their grandparents’ house in the country. All the young cousins were there, and the kids were expected to entertain themselves. Jess thought it’d be cool to do a magazine. “He called it Reader’s Indigestion,” Ralph recalls. “I think I was maybe 4 or 5 years old at the time. He would have been 8 or 9. Jess would have me draw a picture, and that would be one of pages. All the cousins would write something. We had that thing going for probably five or six years. It was just so obvious that Jess was something different. So creative.”

Walter’s childhood publishing effort might not have been so remarkable, Ralph adds, were it not for the milieu in which it was executed. Their Spokane Valley community, he suggests, was a long way from Bloomsbury.

“One day our bikes got stolen,” Ralph says. “I remember being in the front yard with Jess. The kids who stole them rode by — on our bikes — just laughing.” Of course, Ralph also recollects happier moments in the ’hood. Like when the local youth would gather at the Walters’ house, put on oversized boxing gloves and, as Ralph put it, “beat on each other.”

“It was, you know, tough,” he says with a laugh. “You just had to survive.”

Turns out that surviving, or at least developing a thick skin, was key to Walter’s perseverance in his quest to make it in fiction. Even after the success of the Ruby Ridge book, publishers were slow to pick up on his potential.

Walter spent seven long years collecting “no thank you” letters before selling his first piece of short fiction. “Seven years of writing stories, sending them out and getting rejected,” he says. “And it was brutal. But it was also necessary. I wasn’t good enough yet.”

Getting better, Walter believes now, owed much to his newsroom experience. Constant deadlines conditioned him to write — not just when the spirit moved him, but every day, day after day. That’s an essential skill for a novelist, he says. “If you’re waiting for inspiration, you’re not going to write very much.”

Journalism also gave him important insights into our shared human experience, lessons that continue to inform his work today. “I remember early on, I was afraid to interview certain people, to go talk to them,” Walter says. “There was a woman who had been shot to death in a robbery, and my editor wanted me to go talk to her boyfriend. He was living in a little trailer behind the convenience store where she worked. I didn’t want to. He said, ‘Just go. Go talk to him.’”

Walter remembers knocking on the trailer door. “I explained what I was doing. I said, ‘You don’t have to talk.’ And he said, ‘No, no, I’d like to talk.’ So we just sat. He told me about his girlfriend. I took notes. His grief was so profound, and I sat there with my notebook watching him struggle. He’d look around the trailer for help—for some object that might help him describe who this person was, what she meant to him.

“I distinctly remember thinking that the inability to express your deepest emotions is not the same thing as not having the deepest emotions. I thought to myself, ‘This is my job as a reporter: to translate the untranslatable.’”

It’s also been his job as a novelist, especially when it comes to characters who are often far less sympathetic. It’s a skill that other professional writers have long marveled over. One of them, novelist Richard Russo, put it like this: “Here are characters who seem to live of their own volition, who talk out of a terrible inner need to make themselves known and understood, who reveal not just themselves but the yearning heart of our great flawed democracy.”

Walter, who stands all of 5-feet, 10-inches tall, sometimes gets asked what he would have done if he couldn’t be a novelist. “Professional basketball player,” he answers. Maybe not the NBA, he adds, though he admits he long dreamed of becoming a point guard for the Seattle SuperSonics. On this day he’s wearing a SuperSonics t-shirt.

“I imagined myself more as like a small college basketball player. And then maybe I’d become a coach,” he says. “I’m like the second assistant at a liberal arts college somewhere. And my favorite thing about it is that, at this small college, various writers come through, and I get to go sit in the back and imagine being a writer.”

In real life, of course, he doesn’t need to imagine. He’s a full-time professional, writing with both determination and discipline pretty much every day. “I jokingly tell the story that my dry periods tend to lead to a solid chiding in my journal, where I write, ‘You need to get back to work and stop whining,’” he says.

Both the discipline and determination paid off spectacularly with Beautiful Ruins, his 2012 novel that became a surprise No. 1 bestseller, spending months on The New York Times list. The book had been 10 years in the making. Even then, Walter wasn’t sure it was ready.

“He’s always trying to make the work better. He’s never satisfied with just good enough. Jess is one of those writers who just keeps getting better. Every book is better than the last one. That’s rare. I mean, a lot of writers, they have a great book or two and then they kind of plateau.”

Warren Frazier, Walter’s agent at John Hawkins & Associates — the oldest literary agency in the country — has represented him since 2000. Among Frazier’s other clients are Joyce Carol Oates, Adam Johnson, and Robert Olen Butler, all internationally acclaimed novelists.

Frazier remembers the long wait for Beautiful Ruins, reading drafts that he thought were amazing, but that Jess thought weren’t quite there yet. “And I think that’s part of what makes him such a good writer,” he says on a phone call from his office in New York.

“He’s always trying to make the work better. He’s never satisfied with just good enough. Jess is one of those writers who just keeps getting better. Every book is better than the last one. That’s rare. I mean, a lot of writers, they have a great book or two and then they kind of plateau.”

Yet Walter, Frazier continues, keeps pushing, challenging himself, trying new things. “I think that is what’s made his career so successful. Readers can tell that he’s not just phoning it in; not just repeating himself. He’s always trying to do something new, something interesting, something that will surprise both him and the reader.”

The success of Beautiful Ruins, his sixth novel, changed things for Walter. People recognized him on the street. He got calls from Europe wanting him for events. Hollywood asked him to write scripts. It was cool, Walter admits, and he took what he calls “a slightly longer victory lap.” But soon enough he was back at work on Summit Boulevard, hunkered down for hours each day in the “office.”

This is not to suggest Walter is a literary recluse. After finishing a novel, in fact, he’s usually had more than enough “me” time, and welcomes the touring that invariably accompanies new releases. For these events, Walter, a self-professed “extroverted introvert,” says he’s perfected the art of mixing eight minutes of jokes, 15 minutes of reading and 20 minutes of chatting. “I was always kind of a class clown, so to be in front of the class and have people have to listen isn’t the hardest thing.”

What surprises him most about his audiences are their quality, depth and genuine interest in his work: “They’re excited to meet you, and you share this common thing, this book. It’s great fun. Really is one of my favorite parts.” There tends to be lots of curiosity about his process, he adds. Lots of questions about craft, about how he manages to keep moving forward with his work. His advice to aspiring writers is both practical and, unexpectedly, spiritual.

“Read everything. Write every day,” he says. “Don’t wait for permission or validation. And be patient with yourself. Becoming a good writer takes time. The seven years it took me to publish my first story was humbling. But it was also necessary. You have to put in the work.”

But, he continues, try not to think of the work as work. “Treat your writing time the way some people treat their religious practice. Make it sacred. Read that way too — find yourself transported and transcended in the way people are by their faith. One of my great writing times used to be on Sundays. I would trudge out and write on Sunday mornings and then again at night after the kids went to bed (Walter and his wife, Anne, have two children, Ava, now 28, and Alec, 25). Approach writing, I always say, with the same kind of reverence and faith that some people bring to a Sunday service.”

Of course, this being Jess Walter, he punctuates this high-minded counsel with a joke. “When I give this advice, people usually just stare at me, like, ‘All I wanted was your agent’s name.’ So I give them Warren’s name, and we part ways.”

Through it all, Walter has remained deeply connected to his eminently affordable alma mater. His passion for Eastern football and basketball, for example, seems boundless. He’s also contributed to EWU publications (including this one), engaged with student writers, and in 2016 gave a celebrated commencement address to Eastern graduates.

A newly endowed Jess Walter scholarship and writer’s fund, meanwhile, will likely help other first-generation college students who want to pursue writing. He’d love it, Walter says, if it eased the financial stress on some student who followed as unlikely a path as his own.

He is also ramping up his engagement with Eastern in other ways. In February, the university will be honoring Walter with a week-long series of celebrations highlighting his life and work: a public “Evening With Jess Walter” at the Catalyst building; a student symposium on the Cheney campus; an EWU-organized exhibition at the Spokane Public Library on the historical antecedents of Walter’s critically acclaimed 2020 novel, The Cold Millions; and a special shout-out during halftime of an upcoming Eastern men’s basketball game.

These valedictory moments might suggest Walter is resting on his laurels. Nope. Even now, in his sixth decade, Walter shows no sign of slowing down. He’s still thinking about the boxed-up ideas ranged against the carriage house wall. A basketball novel about ambition is in the mix, he says. Maybe a book about Robert Oppenheimer’s self-imposed, post-Manhattan-Project exile in the Caribbean.

What else might emerge? “The next book could be about a circus clown because, who knows what I’ll actually finish?” Does he ever think about taking a break? “Weirdly, if you’re a rock star, no one would have a problem with you pissing off to the south of France to live in a village,” he says. “But I think if you’re lucky enough to get to do this thing for a living, why would you stop?”

These valedictory moments might suggest Walter is resting on his laurels. Nope.

One of Walter’s favorite scenes in So Far Gone portrays a hapless Christian Identity group member who, in the midst of an armed confrontation, is mostly concerned about the well-being of his truck’s new tires. “I just can’t imagine a better way to spend a day than writing a scene like that,” Walter says. “It’s the same reason we read — to be thrilled by some discovery. So much of writing is just play. When I’m thinking like that — when I’m trying to find great sentences— things tend to go well. I always talk about how I take great inspiration from my musician friends, you know? They never say ‘I’m going to work’; they say they’re ‘playing.’”

Jess Walter is still playing. The boxes are still full, and he’s still walking across the lawn to the office every day. The chip on the shoulder is still there, too, that formidable drive to be heard that turned a working-class kid from Spokane into one of America’s finest novelists.

“The thing I fear the most,” he says, “is that I won’t have stories to tell, things to imagine.” Not likely.

Filed Under: Featured

Tagged With: Fall/Winter 2025-26, magazine-featured